Wednesday, May 31, 2023

Alive and Branching Out

Monday, November 16, 2020

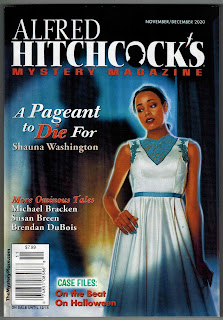

My New Story, "Tamales for Sale," Appears in Latest AHMM

The truth is, I've had little writing news to share. I have been working on a novel -- and then occasionally taking a break to write a story. Speaking of which, I have a new story, "Tamales for Sale," in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine -- the November/December 2020 double issue.

The story centers on a family of undocumented Mexican immigrants in the U.S. -- a grandmother and her adult granddaughter and

grandson -- who cook and sell tamales. The grandmother is a curandera; originally I toyed with the idea of calling the story, "The Curandera's Tamales."

I wrote the story in 2015, which now seems like a totally different era. I don't know if I would've had the nerve to write it today. I aim to treat my characters with respect -- and to render them with detail. I also try to meaningfully capture the challenges the characters face. At the same time, I am not Mexican and have not personally lived with the fear and pressures experienced by the characters.

In 2010, I had a story, "The Docile Shark" in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine that featured a Mexican tour and snorkeling guide, Felipe. The story turns, I hope, on the pathos of Felipe's experience.

Retrospectively, I find myself muddling through these cultural questions about representation and appropriation. I welcome comments and messages to help me along.

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

Scream is Out

When I joined the MWA, I hoped to have lots of leads into anthologies. This expectation didn't entirely pan out, but the MWA does sponsor an anthology most years. (The organization has taken some years off and did a cookbook a few years ago.) I've submitted a few times, but this story is my first MWA acceptance. (Another story that was rejected by the MWA got accepted by a storied magazine; a few others are moldering in drawers.)

"The Trouble with Squirrels" began as a dark story for adults, simply called, "Squirrel." I thought of it as my Roald Dahl-inspired story. I kept the overarching story for "Trouble," but made many, many changes, including transforming my adult protagonist into a curious kid. I also toned down the horror and gore.

In my Portland, Oregon, neighborhood, there is a house whose owner feeds squirrels. Peanut shells strew the property and then radiate outward across the neighborhood. Some years, we are overrun with squirrels. This is the genesis of the story.

While Bob Stine made the final selection of stories, provided a story, and wrote the introduction, the project itself was managed by John Helfers of Stonehenge Editorial. John was a pleasure to work with.

Though Scream published yesterday, I think the bigger promotional push will come in the weeks leading up to Halloween. The movie Goosebumps 2: Haunted Halloween hits theaters on October 12, and maybe this book will try to ride the coattails a bit.

Monday, March 19, 2018

I'm Still Alive

What happened? Well, mostly Goodreads happened. (See the widget to the right.) Instead of posting here, I wrote little book reviews on Goodreads. I guess I should cross-post my Goodreads reviews here -- if I can figure it out.

I also didn't have much news to report. The previous post, for instance, highlights an essay I wrote for The Big Click about Patricia Highsmith. Since then, I haven't had any startling authorial news to report.

But now I do have a small bit of news -- which has been in the works for more than a year. I recently completed copy edits of a story, "The Trouble with Squirrels," which will be published in the Mystery Writers of America anthology, Scream and Scream Again, edited by R.L. "Goosebumps" Stine. The book comes out in late July -- and is really timed for Halloween.

But now I do have a small bit of news -- which has been in the works for more than a year. I recently completed copy edits of a story, "The Trouble with Squirrels," which will be published in the Mystery Writers of America anthology, Scream and Scream Again, edited by R.L. "Goosebumps" Stine. The book comes out in late July -- and is really timed for Halloween.The MWA has been publishing anthologies on and off for many years, but this is the organization's first book for kids. It is also my first story for children -- aimed at middle-schoolers. I'll say more about the story when the book comes out, but since the advance reader's edition is making the rounds, I thought I'd better announce that I'm still alive. I've also set up a contact form (below, to the right), so readers can send me lavish praise.

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

Beastly Murder: A Gossipy Post + Highsmith

After the readings, Alex and I struck up a conversation about AHMM and working with the magazine's editor, Linda Landrigan. (LL has bought one of my stories and sent some kind rejections. She and her Ellery Queen colleague editor Janet Hutchings are actually pretty terrific, but that's another story.) It turned out that Alex was taking up the editorial mantle, guest editing an issue of The Big Click, with the theme "Bête Noire." The catch was that the issue was going to consider real (fictional) animals, not beastly people. We were informally brainstorming -- and I mentioned the James Garner movie They Only Kill Their Masters and Patricia Highsmith's odd and wonderful, Animal-Lover's Book of Beastly Murder. Alex immediately jumped on the Highsmith title and proposed that I write a "fan's review." My critical muscle hadn't been recently exercised and I was "between books" (as it were, waiting for my agent to respond to a current manuscript), so I agreed to the project.

After the readings, Alex and I struck up a conversation about AHMM and working with the magazine's editor, Linda Landrigan. (LL has bought one of my stories and sent some kind rejections. She and her Ellery Queen colleague editor Janet Hutchings are actually pretty terrific, but that's another story.) It turned out that Alex was taking up the editorial mantle, guest editing an issue of The Big Click, with the theme "Bête Noire." The catch was that the issue was going to consider real (fictional) animals, not beastly people. We were informally brainstorming -- and I mentioned the James Garner movie They Only Kill Their Masters and Patricia Highsmith's odd and wonderful, Animal-Lover's Book of Beastly Murder. Alex immediately jumped on the Highsmith title and proposed that I write a "fan's review." My critical muscle hadn't been recently exercised and I was "between books" (as it were, waiting for my agent to respond to a current manuscript), so I agreed to the project.Rereading Highsmith and writing "The Friendly Animals of Patricia Highsmith: An Appreciation of The Animal-Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder" turned out to be a lot of fun. The piece went live last week -- so check it out on The Big Click. The bonus was getting to hang out with the super-terrific Alex and her posse of other writers. As I said, the moral of the story is that I should get out more often.

Tuesday, January 27, 2015

The Anguish of Plot in Dobyns and Temple

Late last year, I read two very different crime novels that ended up reminding me of one another because of the similar tension between the plot imperatives of crime fiction and the writers' interest in other matters, primarily fleshing out protagonists beyond the core plot. The two books are Stephen Dobyns's 1983 novel Dancer with One Leg (which I think is a great title) and Peter Temple's 2005 novel The Broken Shore. Both are strong books, though I preferred Dancer, as I'll explain.

Late last year, I read two very different crime novels that ended up reminding me of one another because of the similar tension between the plot imperatives of crime fiction and the writers' interest in other matters, primarily fleshing out protagonists beyond the core plot. The two books are Stephen Dobyns's 1983 novel Dancer with One Leg (which I think is a great title) and Peter Temple's 2005 novel The Broken Shore. Both are strong books, though I preferred Dancer, as I'll explain. The Broken Shore is set on the other side of the world -- in eastern Australia -- in a provincial town, with forays to Melbourne. Like Lazard, police detective Joe Cashin is also a damaged soul. Before the novel opens, a junior partner had been killed and Cashin badly injured on the job. He is still haunted by this incident and by his difficult upbringing. His dotty mother and estranged brother both figure in the novel. Cashin has relegated himself to the provincial police force as part of his recovery. With the assistance of a tramp he takes in, he also works at restoring a family property.

The Broken Shore is set on the other side of the world -- in eastern Australia -- in a provincial town, with forays to Melbourne. Like Lazard, police detective Joe Cashin is also a damaged soul. Before the novel opens, a junior partner had been killed and Cashin badly injured on the job. He is still haunted by this incident and by his difficult upbringing. His dotty mother and estranged brother both figure in the novel. Cashin has relegated himself to the provincial police force as part of his recovery. With the assistance of a tramp he takes in, he also works at restoring a family property.Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Facing January

I had this idea that in 2015, I might return to writing this blog after a long, desert-wandering absence. I've been writing about my reading on Goodreads -- see the feed to the right -- but thought I might expand here with some further observations (but not in this post). I also, uncharacteristically, wrote a long semi-commissioned "fan review" recently on Patricia Highsmith's strange and unique story collection, The Animal-Lover Book of Beastly Murder. I'll post an announcement when it's published.

I had this idea that in 2015, I might return to writing this blog after a long, desert-wandering absence. I've been writing about my reading on Goodreads -- see the feed to the right -- but thought I might expand here with some further observations (but not in this post). I also, uncharacteristically, wrote a long semi-commissioned "fan review" recently on Patricia Highsmith's strange and unique story collection, The Animal-Lover Book of Beastly Murder. I'll post an announcement when it's published.As I was working on the Highsmith piece -- and finding a little creative reinvigoration -- the film adaptation of her 1964 novel, The Two Faces of January, hit the theaters. It's been a while since I read the book, but the film nicely captures the novel's desultory criminality and morbid, complex attraction between the two male characters, Rydal (Oscar Isaac) and Chester (Viggo Mortensen). The film aims to tie up the plot a little more neatly than Highsmith's novel, but let's blame the film industry for that. If I recall correctly, Highsmith's American publisher (Harper) actually turned down the novel, which irritated Highsmith to no end (naturally), and she had to change publishers. She felt vindicated when the novel ended up winning the Gold Dagger for Best Foreign Novel from the UK's Crime Writers' Association (CWA).

The film also uses its locations -- notably Crete -- especially well. Highsmith readers/critics rightly focus on her strange characterization, but it's worth remembering that she made great use of locations and geography -- Greece in Two Faces, but also Venice in Those Who Walk Away and Tunisia in The Tremor of Forgery.

Highsmith was one of my original inspirations for getting serious about my own writing. Her book on the craft, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, may not be exactly useful, but I found it interesting. (For instance, she remarks (to the chagrin of editors and agents everywhere), "I like a slow start.") Her works gain depth by breaking certain rules: notably, motivation is never quite clear, and characters are not exactly consistent. Arguably, these characteristics make her novels seem both more artificial and more realistic. Perhaps this dynamic keeps some of us reading.

Sunday, February 9, 2014

Return of the Prodigal Blogger... and Westerns

First--and I have said this before, but I think my intent might stick--I am setting aside my war reading (and I'm going to take "Writing on War" off my masthead soon). To be an engaged citizen of sorts, I believe that it is important to be historically informed and perhaps know a bit about the experience and cost of war. That said, I've come to believe that my extended dive into war writing -- fiction and non-fiction -- was not entirely healthy for me, or it reflected something unhealthy (it was perhaps both causal and symptomatic).

So, since September, I've been reading all over the place, but not crime/mystery fiction so much. I've been reading some metaphysics and also Westerns. My agent has in mind that I might write a Western (he also had me write a synopsis of a post-apocalyptic Stephen King meets Michael Crichton sort of novel; everything is up in the air). I'd read a few Westerns before, but not many, and so I've been reading some lately -- and enjoying them much more than I had expected: Elmer Kelton, Louis L'Amour, Glendon Swarthout, and others.

So, since September, I've been reading all over the place, but not crime/mystery fiction so much. I've been reading some metaphysics and also Westerns. My agent has in mind that I might write a Western (he also had me write a synopsis of a post-apocalyptic Stephen King meets Michael Crichton sort of novel; everything is up in the air). I'd read a few Westerns before, but not many, and so I've been reading some lately -- and enjoying them much more than I had expected: Elmer Kelton, Louis L'Amour, Glendon Swarthout, and others.  First and foremost: L'Amour and Swarthout, what I've read so far, write really well: sharp prose, good characterization and action, etc. I think I was put off by the excessive branding (and sheer volume) of L'Amour, but it turns out -- at least based on the two titles that I read (Hondo and Down the Long Hills) -- that he deserves his reputation. In general too, in the Westerns that I've read, I've liked the heroic nature of the main characters and the lack of irony. I might just be on a sincerity kick.

First and foremost: L'Amour and Swarthout, what I've read so far, write really well: sharp prose, good characterization and action, etc. I think I was put off by the excessive branding (and sheer volume) of L'Amour, but it turns out -- at least based on the two titles that I read (Hondo and Down the Long Hills) -- that he deserves his reputation. In general too, in the Westerns that I've read, I've liked the heroic nature of the main characters and the lack of irony. I might just be on a sincerity kick.Small News

On February 24, Crime City Central will be podcasting a story of mine, "Bridget's Conception." If you're amenable to the audio delivery of stories, please listen and let me know what you think.

Friday, August 16, 2013

"Rake" Made Me Laugh

And sure enough, Phillips notes the influence of Willeford (and Highsmith) in this nice little L.A. Times interview: "Scott Philips Talks About his Novel 'Rake.'" If you like the offbeat, amoral humor of Willeford, you'll like Phillips's writing, too.

Rake is narrated by an unnamed American actor -- the star of a soap opera that has taken off in France -- as he traipses around Paris, signing autographs, bedding women, beating up wayward youth, and seeking financing for his movie. Even as he becomes embroiled in various criminal activities, he keeps chasing tail, working crossword puzzles, and getting a good night's sleep. Phillips continually mines humor from his protagonist's libido and insouciance. As a side note, the book is also a sort of love letter to Paris (Phillips lived in France for a time).

Rake is more of a lark than Phillips's previous work, The Adjustment (follow link for my review of that). I hope his writing doesn't become too madcap, but then, Phillips is pretty damn funny.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

Detroit: An American Autopsy

Detroit belongs alongside Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt. Like DDDR, LeDuff's history/memoir charts part of America in decline (or rock bottom) -- in this case, what was once a model city and industry. The auto industry built Detroit, and the city swelled to about 1.2 million people in the 1950s. Today, about 700,000 people live there. This means blocks of buildings are left derelict and uninhabited. The loss of tax base, of course, contributed to Detroit's financial downfall.

But Detroit's undoing has also come at the hands of elected officials, entrenched judges, corruption, mismanagement, and so on. LeDuff in particular discusses two crooked, pitiful, but sometimes colorful fallen elected officials -- both of whom served time in prison: Former Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick and City Council Member Monica Conyers (wife of U.S. Rep. John Conyers).

Detroit also has plain bad luck and consistently picks losers. For instance, when a tough chief of police was ousted, he was replaced by Ralph Godbee, who "took a kinder, gentler approach to policing." The murder rate subsequently went up, the police renewed fudging crime stats, and part-time preacher Godbee ends up resigning after bedding "a bevy of female officers." Other losers picked by the Detroit: the Key to the City was given to tyrants Saddam Hussein and Robert Mugabe.

LeDuff's book is as much memoir as history or journalism. He charts his own family's history in the Detroit area, including the unnatural deaths of his street-walking sister (drunken accident) and niece (OD). LeDuff's close personal investment in his story provides emotional -- but not sentimental -- weight. At the same time, the title is a little misleading since it primarily offers recent snapshots of Detroit -- not quite a full autopsy. Another book with the same title, for instance, might've proposed more solutions or examined certain public policies (e.g., causes of death) more directly. But no matter, this is a powerful book that shows how far an American city can fall -- and how far it will have to go to recover.

Sunday, June 30, 2013

A New Look at the Vietnam War: Nick Turse's "Kill Anything that Moves"

Based on Turse's doctoral dissertation -- and painstakingly researched and sourced, though very readable -- this book has a central thesis: The American way of war in Vietnam resulted in mass killings of civilians in South Vietnam. The My Lai massacre was but one example of thousands of days of misery visited upon the people of Vietnam. The conditions that made war crimes possible were created at the highest levels of government and military command.

Now, 40 years or so from the wind-down of the war, Turse's observations might seem matter-of-fact. We all know how horrible Vietnam was (though usually we think of U.S. soldiers, not Vietnamese civilians), but what this book details is the pervasiveness of wanton murder of unarmed civilians throughout the course of the war.

Ultimately, it was policies and politics that drove the carnage. By early 1971, Telford Taylor, a retired army general who served as chief counsel at the Nuremberg trials, said in a nationally televised interview that Westmoreland might well have been prosecuted for war crimes. A field general, Julian Ewell, and his executive officer Ira Hunt were the primary proponents of pushing "body counts," which led to indiscriminate civilian killing in the populous Mekong Delta in late 1968 and 1969 -- in an operation called Speedy Express. Unarmed civilians were subject to artillery fire, helicopter attacks, and ground troop invasion. Civilians were shot for running from the approach of soldiers. The dead were inevitably counted as Vietcong, but consider one fact uncovered by a team of Newsweek reporters: Ewell's division reported killing 10,899 enemy troops, yet it recovered only 748 weapons. At one point 699 "guerrillas" were killed, but only 9 weapons captured. These non-correlative numbers indicate widespread killing of unarmed civilians.

Did the U.S. military care? In fact, Turse draws heavily on declassified documents from the Pentagon's War Crimes Working Group, which was set up in response to My Lai. Turse explains: "The group did not work to bring accused war criminals to justice or to prevent war crimes from occurring in the first place. Nor did it make public the constant stream of allegations flowing in from soldiers and veterans. As far as the War Crimes Working Group was concerned, these allegations were purely an image management problem..."

The policies and the cover-ups are what's central here. While Turse rightly lauds reporters like Seymour Hersh (whose writing broke the My Lai story), he also notes that the press sat on or effectively killed stories. (And hey, the New York Times hasn't reviewed this book, which seems unbelievable.) In 1972, Newsweek's Saigon bureau chief Kevin Buckley wrote, in part, "Four years here have convinced me that terrible crimes have been committed in Vietnam. Specifically, thousands upon thousands of unarmed, noncombatant civilians have been killed by American firepower. They were not killed by accident. The American way of fighting this war made their deaths inevitable." This lead was killed and the article watered down, and Speedy Express is now hardly known.

While Turse focuses on leadership, policy, and cover-ups, he also carefully documents atrocity after atrocity. There is the West Point colonel who hunts Vietnamese from his command helicopter, the decorated sergeant whose wildcat team kills and mutilates civilians, the personnel who routinely torture, and on and on. Turse looks at sexual crimes and South Vietnam prison conditions as well.

Many hard facts and figures back up Turse's points. Did the U.S. have a plan to help the people of Vietnam, so they would turn from communism (or nationalism or patriotism)? One telling figure: In 1967, USAID's total medical budget to support health programs in Vietnam equaled 0.25% of the total U.S. spend in the nation.

So, where does this leave us? Turse makes clear that we have not adequately assessed Vietnam -- and that failure continues to haunt our foreign policy and military.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Knife Music: Good Book, Problem Reader

At times, I feel like a reader (and filmgoer) with the opposite problem -- little grabs or excites me. I start books and don't finish them. I'm lukewarm about movies that others rave about. It's a problem, then, if I want to offer my views with a good semblance of fairness. (When I was younger and brash, I might've argued for critical "objectivity," but not anymore.)

All of which brings me to David Carnoy's Knife Music. This is a good, entertaining book -- certainly worth noticing; I sucked it down in just a few days. It's the story of hotshot, semi-womanizing ER surgeon Ted Cogan who is (wrongly?) accused of the statutory rape (which is just plain rape in California) of a teenage patient. Cogan is a complex character, sympathetic yet cold, well-off and resourceful but in deep trouble. He's pitted, in part, against a dedicated police detective, Hank Madden.

All of which brings me to David Carnoy's Knife Music. This is a good, entertaining book -- certainly worth noticing; I sucked it down in just a few days. It's the story of hotshot, semi-womanizing ER surgeon Ted Cogan who is (wrongly?) accused of the statutory rape (which is just plain rape in California) of a teenage patient. Cogan is a complex character, sympathetic yet cold, well-off and resourceful but in deep trouble. He's pitted, in part, against a dedicated police detective, Hank Madden.While I semi-feverishly turned the pages of Knife Music, it also lagged in a few areas. First, too much backstory -- especially a chapter about Cogen. And too much detail. I'm on thinner ice here. The mystery writer needs a certain amount of detail to bury clues, and detail creates "l'effet de reel" (to fall back on my weak Roland Barthes). But when is extra detail too much? Consider, for instance, that Madden spies on Cogan "through a set of compact but powerful Nikon binoculars." I would've settled for "compact" and assumed that the cop had a good enough pair of binoculars for his job; I didn't need the brand. The book seems too full of this minutia. But maybe this is just me being cranky?

Though Cogan faces the prospect of an ugly, public trial and jail, he never seems in too much jeopardy. The book is set in the wealthy environs of Silicon Valley, with jaunts to the Stanford campus, a gated community, and a country club -- wealthy but not Sternwood-wealthy. Is there some sourness to this world of privilege, something that might be exposed? Carnoy succeeds with an engaging breezy novel. Should I fault him because I wanted rougher weather?

Friday, April 12, 2013

News Flash: Bear Serves in World War II

I missed a month, but I'm back. My reading is varying widely, and though I swore off war books after reading We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families, I made an immediate exception for Soldier Bear by Bibi Dumon Tak, which I read for my younger daughter's library book group.

I missed a month, but I'm back. My reading is varying widely, and though I swore off war books after reading We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families, I made an immediate exception for Soldier Bear by Bibi Dumon Tak, which I read for my younger daughter's library book group.Soldier Bear is a young reader's novel based on the true story of a Syrian brown bear adopted by a group of Polish soldiers during World War II. Wojtek (or "Voytek," as the bear is called in the English translation from the Dutch) is a cute nuisance, but he eventually wins over various officers and even helps carry artillery shells. The bear accompanies the soldiers (aligned with British forces) from Egypt to Italy, where he serves near the front in a transportation company.

A central critical question seemed to hover over my reading of this book: "How do you write a book about war for young kids?" While earnest and heartfelt, Soldier Bear offers only a few tough insights into the war. One soldier, Lolek, is traumatized when he sees two soldiers killed by a bomb, but this is the only human death we see (there are other animals, too). In the end--and perhaps justifiably, considering the intended audience--Soldier Bear is more of an animal yarn than a war novel. It made me think of the animal books of Gerald Durrell (which I really don't remember, so the comparison might be off). The book also never quite emotionally captures the daily grind, boredom, and fear that fill out a soldier's everyday life. In some regards, the characters and the storytelling are a little flat.

A central critical question seemed to hover over my reading of this book: "How do you write a book about war for young kids?" While earnest and heartfelt, Soldier Bear offers only a few tough insights into the war. One soldier, Lolek, is traumatized when he sees two soldiers killed by a bomb, but this is the only human death we see (there are other animals, too). In the end--and perhaps justifiably, considering the intended audience--Soldier Bear is more of an animal yarn than a war novel. It made me think of the animal books of Gerald Durrell (which I really don't remember, so the comparison might be off). The book also never quite emotionally captures the daily grind, boredom, and fear that fill out a soldier's everyday life. In some regards, the characters and the storytelling are a little flat.My older daughter--a junior in high school--is in a Vietnam War class, and they are reading Tim O'Brien, Ron Kovic, and others. Though war reading can be tough, it makes sense since these students are on the cusp of enlistment/selective service age--and will soon by voters. Even younger students read All Quiet on The Western Front, which might be misguided. It's a terrifying, vivid book--no Soldier Bear--and shouldn't be relegated to high school freshmen English. (I'll note too in passing that in my post on All Quiet, I wrote, "I'm going to try to wind down my war reading for a bit," and that was in November 2010. Now, I'm really going to try--maybe I'll switch to books about urban blight, poverty, and general misery.)

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Required Reading: We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will Be Killed

Now, in what feels like a culmination and maybe a stopping point for a while, I’ve read Philip Gourevitch’s We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families: Stories from Rwanda (1998). It has shaken me, and in its way, shamed me. For World War II and Vietnam, I can assume the role of an historic observer. I remained more or less informed on and voted with a mind toward policy in Iraq and Afghanistan. But I think I ignored the events in Rwanda as they were happening and being reported. During the genocide in Rwanda, I believe I was teaching an introductory course on epic, working on my doctoral dissertation, riding my bike, and generally lazing about. I neglected the pious Hebrew school adage about genocide—“Never again.” I didn’t even muster much awareness.

We Wish (I’ll use this shortened title) surely indicts my neglect. But certain actions—well-intentioned humanitarian actions—were worse than neglect in that they ended up aiding and abetting the genocidaires (the French term used for the Rwandan mass killers). It turns out, too, that the U.S. utterly neglected its obligations under UN General Assembly Resolution 260, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Clinton expressed regret that he had not intervened (and he was the first western leader to visit Rwanda after the genocide). Gourevitch writes that then-U.S. Ambassador to the UN Madeleine Albright’s “ducking and pressuring others to duck [intervention], as the death toll leapt from thousands to tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands, was the absolute low point in her career as a stateswoman.”

If American inaction is retrospectively reprehensible, then French support for Hutu Power is even worse. Belgian colonialism played a fundamental role in creating an environment for genocide. Many religious organizations and their leaders, at least within Rwanda, supported the genocide as well.

The UN was awful. The Canadian head of the UN force, Romeo Dallaire, was repeatedly thwarted in his effort to intervene more forcefully. Though the UN prevented the massacre of some people, Dallaire later asserted that 5,000 well-equipped soldiers may have been able to prevent a half million murders.

I think I might’ve held the common misperception that the genocide was a sort of uncontrolled spontaneous mob spasm of racial killing. Chaos in a failed African state. From this point of view, it is easy to think that military and political intervention would have been futile. In fact, Rwanda was a well-organized country with a government that planned the killing well in advance, promoted it on radio and in print, and enforced its execution. Consider this: in the months leading up to the genocide, the government imported machetes from China and distributed them to the majority Hutu population for the express purpose of exterminating the Tutsi minority. In 100 days, 800,000 to a million people were killed.

|

| Dessicated bodies at the Murambi Genocide Memorial Centre |

Recovery in Rwanda, in Gourevitch’s account, is at least buoyed by compassionate and sensible leadership, embodied by then-General Paul Kagame (who has been Rwanda’s President since 2000). Gourevitch describes Kagame as part of a post-postcolonial era that views the west with healthy skepticism.

Late last year, I heard a presentation by Doctors Without Borders (Medicines Sans Frontieres or MSF), and its representatives spoke about the dangers of aid being used as a weapon of war. In Rwanda and cross-border refugee camps, this was certainly the case. Thus certain types of humanitarian aid are counterproductive—an argument that writer (and onetime Ugandan resident) Paul Theroux also makes in Dark Star Safari (which I reviewed back in 2002). So where does that leave a concerned westerner? I don’t know.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Joe Sacco: Comics Journalism and Conflict

I started with Sacco's recent work in Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt, which is primarily made up of text written by Chris Hedges (discussed in my previous post). I like Sacco's work in this book, but Hedges's text plays the starring role.

In Sacco's most acclaimed books (and all his own), Palestine and Safe Area Gorazde, all the text is provided in comics panels. The images convey as much meaning and drama and reportage as the words. Unlike traditional journalism, Sacco is part of the story: his thin, worried figure makes its way through muddy streets in war-torn Bosnia (1992-95) or the West Bank or Gaza Strip (from 1990-91). We see him as outsider impacting the story -- and he also stands in for us -- amazed and befuddled at the destruction and survival of the places he visits.

I'm not a comics or graphic novel aficionado, but I would say that Sacco's drawings are loosely in an R. Crumb style, but a little more realistic (in his later works) and finely detailed. Sacco's birds-eye panoramas are especially compelling, showing wide angles and bustling activity that aren't usually caught in a photograph. Perhaps an apt comparison would be Brueghel. To my mind, the tension between the subject matter -- serious and deadly -- and the comics style gives the work great vitality.

Sacco mostly focuses on the nature of civilian life in conflict-torn areas. He also provides some history and context, especially in Gorazde. The U.N. comes off very poorly.

Sacco doesn't have a website, though you can find some images online. It's far better to dive into the over-sized books. I've included a couple of covers and one author self-drawing (much like what appears in his books; taken from the publisher Drawn & Quarterly's website). I believe this constitutes fair use, but I want to respect copyright, so if image owners (e.g., Sacco, his publishers) want images removed, please say so in the comments.

Monday, December 31, 2012

War and Sacrifice Zones

Filkins's book snuck up on me. Published in 2008, it covers primarily combat and sectarian violence in Iraq following the invasion. It is not, however, a history or a piece of straight-up journalism (Filkins was a reporter for the LA Times and then the New York Times). Instead, it mixes reporting with personal narrative -- the weirdness and disjointedness of the places and the war are reflected by Filkins's telling.

The first part of the book recounts some of Filkins's experiences in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan before 9/11. In a soccer stadium in Kabul, Filkins witnessed the amputation of a man's hand (for theft), and the execution of another man (for murder/manslaughter). The Taliban were warily accepted by people in Afghanistan because they brought some social stability and security to a fragmented country (headed towards the anarchy of Somalia). In Filkins's reckoning, the future of Afghanistan will be either bad or worse.

The first part of the book recounts some of Filkins's experiences in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan before 9/11. In a soccer stadium in Kabul, Filkins witnessed the amputation of a man's hand (for theft), and the execution of another man (for murder/manslaughter). The Taliban were warily accepted by people in Afghanistan because they brought some social stability and security to a fragmented country (headed towards the anarchy of Somalia). In Filkins's reckoning, the future of Afghanistan will be either bad or worse.Filkins's take on Iraq is slightly more hopeful, but not by a lot. Rather than drawing broad conclusions, Filkins primarily recounts his experiences and lets them speak for themselves. Though the U.S. has obvious combat superiority -- and Filkins describes Falluja at its worst -- it has limited political and diplomatic capabilities. The U.S. was never going to be able to transform the country working from the isolation of the heavily fortified Green Zone in Baghdad.

Filkins, to a certain extent, followed in Hedges's footsteps. Hedges was also a New York Times war correspondent. He covered wars in Latin America, reported from inside the siege of Sarajevo, and wrote from several other war zones. Earlier this year, I read Hedges's philosophical distillation from all his war reporting, War Is A Force That Gives Us Meaning (2002). Hedges essentially lost his Times job for publicly opposing the invasion of Iraq.

In Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt, Hedges and Sacco (with Sacco illustrating) examine four U.S. "sacrifice zones" -- places ravaged by power, capitalism, and environmental degradation. The zones are Pine Ridge Indian Reservation; Immokalee, Florida; Camden, New Jersey; and coal mining areas of West Virginia. The last chapter discusses the Occupy movement, with a focus on New York.

Hedges and Sacco have given up on the electoral system and the Democratic Party -- they call for dissent, obstruction, civil disobedience, and a rejection of consumer society. Hedges has seen war and revolts around the world, and he argues that the U.S. is in the midst of a slow-burn revolution -- though it is a revolution that could very well fail. It was alarming and invigorating to read what is very much a modern day jeremiad. This book is full of anger, lament, and indictment. Frightening.

Friday, December 7, 2012

Blank Spots, Secrecy, Aesthetics, and Trevor Paglen

These titles are arguably a little misleading, or at least limiting, because the books aren't really straight-up exposés of the Pentagon. Each book is quite different, but together they focus on the culture, significance, and resonance of secrecy in American politics, warfare, law, architecture, and geography.

Military Patches

The first book, I Could Tell You..., is small, seemingly incidental, and something of a curiosity. The cover actually bears a machine-sewn, circular patch with the book's title, similar in style to the military and secret program patches featured in the book. Paglen begins with a short history of military patches -- beginning with the American Civil War -- and then discusses the contradiction of patches that call attention to programs that are secret. In part, the patches build camaraderie -- and they also serve as real warnings to other people on a particular base. A patch -- worn by members of the 22nd Military Airlift Squadron -- that says "Don't Ask! NOYFB" means just that.

The patches include a mixture of iconography, though in similar styles. Several have skeletons: the wearers bring death. Many have ghosts or cloaked figures: secrecy. Some have animals -- references to project names or Lockheed's Skunk Works. Eyes for spying and surveillance. We see a lot of Latin phrases on patches, including a convoluted passive phrase that gives the book its title. The patches are at once kitschy, mysterious, and deeply chilling. This volume serves as a nice prologue to the secret world more fully described in the second book, Blank Spots.

Uncovering the Secret World

While Paglen describes himself as an artist (a complex issue -- see discussion below), Blank Spots has few images -- just one photo at the start of each chapter. Instead, the book charts Paglen's own varied fascination with secrecy in various manifestations. The son of an Air Force doctor, Paglen grew up on and around various bases, where he occasionally encountered adults with mysterious civilian and military duties. Once, the father of a friend was dropped off at work -- at the edge of a corn field into which he disappeared.

While Paglen describes himself as an artist (a complex issue -- see discussion below), Blank Spots has few images -- just one photo at the start of each chapter. Instead, the book charts Paglen's own varied fascination with secrecy in various manifestations. The son of an Air Force doctor, Paglen grew up on and around various bases, where he occasionally encountered adults with mysterious civilian and military duties. Once, the father of a friend was dropped off at work -- at the edge of a corn field into which he disappeared.As a graduate student in geography at UC Berkeley (my own alma mater) -- working on the siting of prisons (once urban as a warning, now rural to go unnoticed and forgotten) -- Paglen increasingly noticed that "vast swaths of land, particularly in the Nevada desert, were missing from imagery collections." Blank spots on maps are not new, we learn. In the age of exploration, maps could contain state secrets and so they were closely guarded. But Paglen is surprised to find that this phenomenon remains true today.

You can immediately see what Paglen means by visiting Google Maps or Bing Maps. Look at Nevada. You'll see blank spots in various chunks of the state, notably to the northeast of Las Vegas, where experimental aircraft are tested.

Paglen's initial interest leads him to hunker down in a hotel room in Vegas, photographing unmarked "Janet" planes (737s) that ferry ordinary-looking workers to jobs at black sites deep in the Nevada desert. He also wrangles an invitation to a celebratory dinner thrown by the Flight Test Historical Foundation at Edwards Air Force Base, where three test pilots are honored for work on recently declassified projects. Paglen discovers "blank spots" in the program -- huge pieces of the pilots' biographies are missing because they worked on projects that remain classified. As the book progresses, we find blank spots in the federal budget (arguably a violation of the Constitution), blank spots in the catalogue of satellites and debris circling the earth (space-track.org), enormous blank spots in history.

Paglen takes a step back to examine the historic rise of the modern culture of secrecy, beginning with the Manhattan Project. I offhandedly asked three educated, informed family members how many people they thought were employed by the Manhattan Project: two answered 1,000 and one said 10,000. These seem like fair guesses to me, and I might have said something similar. In fact, at its peak, the Manhattan Project employed more than 130,000 people. "It represented an industrial sector equal in size to the entire American auto industry." And yet this substantial industry remained unknown to the public, the courts, the media, and most of Congress.

The secret world grew substantially during the Cold War, except for a minimal retreat around Watergate. Its growth included legislation and court rulings, each discussed in the book. It expanded again at a terrific pace during the recent Global War on Terrorism. Today's key blank spots for Paglen are secret prisons that exist outside the law. He photographs one on the outskirts of Kabul. According to Paglen, approximately 4 million people in the U.S. hold security clearances to work on classified projects (the "black world"). By contrast, the federal government employs about 1.8 million people in what Paglen calls "the white world."

Aesthetics, Secrets, and Revelation

Blank Spots is mixture of primary and secondary history, investigative journalism, personal rumination, and more. Ultimately, Paglen has a point -- that secrecy undermines democracy and provides a foundation for the abuse of power.

But Paglen recently seems, at least partially and vaguely, to abrogate his own authority by identifying himself as an artist. And he is an artist -- by what he produces (photographs), by how he makes his living (grants and selling photos as art), and by his credentials (he has an MFA from the Art Institute of Chicago, on top of his Berkeley Ph.D. in Geography)).

In a tricky, mercurial (even secretive) stance, Paglen uses his aestheticism to step back from what might be the material impact (e.g., real-world change) of his work. For instance, in an interview in The Rumpus, Paglen casually notes that his long-distance photos of secret bases are "not produced in order to be evidence of some kind, or to reveal any kind of information at all. These are art photos." This is a statement of art for art's sake, for the value of the photos in and of themselves, as objects of beauty. I want to protest, though, that his photos are informed by a material agenda, in his words "to prevent the secret state from spreading."

But ultimately, it is worth understanding Paglen's retreat or progression toward art. Blank Spots, in its way, is a completed project, but he continues to photograph secret sites. There is something compelling -- regardless of politics -- about secrecy and revelation. The parallel existence of worlds seen and unseen, side by side, resonates; it excites the mind. It is the stuff of science fiction (think of The Matrix or "The Force"), mystery and crime fiction, the traditional and neo-gothic (think of Blue Velvet).

From Paglen's website: "Trevor Paglen's work deliberately blurs lines between science, contemporary art, journalism, and other disciplines to construct unfamiliar, yet meticulously researched ways to see and interpret the world around us." What I find compelling here is that Paglen is charting a space in which his art exists for its own value but also simultaneously, separately, and deliberately does political (but not polemical) work.

As a postscript, I'd be curious to hear Paglen's take on secrecy outside government. Secret societies? Corporate and trade secrets? Arguably, the concept of the "secret" Coke formula adds value to the brand -- and then to the experience of drinking the soda. And so on.

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Two American Books Born of Iraq

After an absence here, I am back -- but with a familiar topic: war. I stepped away from reading war books, but a couple found me recently, and so I read them. I find this happens when the days get short.

Kevin Powers and Brian Castner both served in Iraq, Powers as an enlisted Army machine gunner and Castner as an Air Force (captain) explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) officer -- a bomb tech. Powers -- who has an MFA (and was a Michener Fellow in Poetry) has written a short, dense, harrowing, bloody novel, The Yellow Birds. Castner, who has a degree in electrical engineering, has written a short, dense, harrowing, bloody memoir, The Long Walk: A Story of War the Life that Follows. Together, the books make for a dismal and meaningful pair, two snapshots of warfare gone especially bad.

First, Castner. The

Long Walk is divided by alternating sections of the past and near-present

time. Castner recounts being briefed,

while on duty in Saudi Arabia after 9/11, about how to turn off certain nuclear

bombs that intelligence believed had been acquired by Osama bin Laden. After the demonstration, Castner writes,

"Now I knew what I wanted to be when I grew up." His passion, it turns out, is heroic but unavoidably

destructive. For Castner, the work is

physically damaging and psychically scarring.

A good deal, if not the majority, of the mental damage has physical

roots -- traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by proximity to scores (hundreds?)

of explosions.

First, Castner. The

Long Walk is divided by alternating sections of the past and near-present

time. Castner recounts being briefed,

while on duty in Saudi Arabia after 9/11, about how to turn off certain nuclear

bombs that intelligence believed had been acquired by Osama bin Laden. After the demonstration, Castner writes,

"Now I knew what I wanted to be when I grew up." His passion, it turns out, is heroic but unavoidably

destructive. For Castner, the work is

physically damaging and psychically scarring.

A good deal, if not the majority, of the mental damage has physical

roots -- traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by proximity to scores (hundreds?)

of explosions. Castner arguably approaches his condition and experience

like an engineer -- with structure and analysis. By contrast, in The Yellow Birds, Powers continuously flexes his

poetic capabilities. His prose is rhythmic,

sensory, adjectival. Rivers and water

and blood thread their way through the book, and the writing often has a

sinuous quality. Yet, ultimately I

(first person, sensitive here to my subjectivity) found these qualities distancing my

mind from the story, from the soldier's experience in Iraq. Powers book has been very highly praises and

was a finalist for the National Book Award.

It is worth reading, and at its heart, it tells a tragic story of the

narrator's guilt and unraveling following the death (not a spoiler) of his

comrade. For me, though, the highly

aestheticized telling of the story weakens its emotional impact.

Castner arguably approaches his condition and experience

like an engineer -- with structure and analysis. By contrast, in The Yellow Birds, Powers continuously flexes his

poetic capabilities. His prose is rhythmic,

sensory, adjectival. Rivers and water

and blood thread their way through the book, and the writing often has a

sinuous quality. Yet, ultimately I

(first person, sensitive here to my subjectivity) found these qualities distancing my

mind from the story, from the soldier's experience in Iraq. Powers book has been very highly praises and

was a finalist for the National Book Award.

It is worth reading, and at its heart, it tells a tragic story of the

narrator's guilt and unraveling following the death (not a spoiler) of his

comrade. For me, though, the highly

aestheticized telling of the story weakens its emotional impact.Wednesday, September 19, 2012

Recovered -- and Refreshing -- Noir

I'm not a noir or Gold Medal Books expert, so it's hard to know if that moldering paperback with a lurid cover will be any good. You can bet on some authors -- e.g., Charles Williams -- but others haven't aged well or were never very good to start with. Fortunately, there are experts like Bill Crider and Ed Gorman, and imprints like Stark House Noir Classics.

I'm not a noir or Gold Medal Books expert, so it's hard to know if that moldering paperback with a lurid cover will be any good. You can bet on some authors -- e.g., Charles Williams -- but others haven't aged well or were never very good to start with. Fortunately, there are experts like Bill Crider and Ed Gorman, and imprints like Stark House Noir Classics.And so, a single volume with two pretty great titles -- One is a Lonely Number (1952) by Bruce Elliott and Black Wings Has My Angel (1953) by Elliott Chaze -- found its way into my hands. Each novel tells the story of a man on the lam who falls for a dame. In its way, Lonely Number seems the more transgressive because the dame is a 14-year old with epilepsy. But antihero Larry Camonille is a nice guy who is willing to take the extra step to see that she gets the medical care she wants.

Black Wings is the longer, more romantic, introspective book. Kenneth McClure -- alias Tim Sunblade -- is smart, disciplined, and brutal. He hooks up with a mysterious, high-class call girl who likes it rough. He puts together a great heist, but this is a Noir Classic, so...

In today's era of heroes, series books, and good luck, it's refreshing as hell to read grim, nasty, feverish, morally unhinged novels of men and women who don't seem particularly destined to make it to a sequel.

Friday, August 24, 2012

The Other Jack Black Can't Win

Originally published in 1926, You Can't Win recounts Black's life from boyhood to career criminal to prisoner and then to ex-con reformer. From about the age of 15, Black led a rail-riding, transient life and easily fell into the career of a house burglar and safe robber. Black writes a fair amount about the code among criminals, the "Johnson" family who do right by one another. Black also has pride in his craft and a work ethic of sorts. He is once terribly chagrined when an ex-robber suggests he take a straight job.

The memoir has many interesting parts that are nearly lost history. Black became a habitual opium smoker -- in part to calm the nerves that come from house burgling -- and then a sick addict. Thus the book is an important source for Martin for his opium book. It was also championed and introduced in a later edition by William S. Burroughs.

The memoir also offers several portraits of prisons, jailers, and penal systems. Black does relatively well -- and reads widely -- in a Canadian prison, but no talking is allowed at all. For calling out to a friend, Black is put on bread and water. He also describes receiving two lashings at the start and end of one prison stint; the lashings are actually part of the Canadian judge's sentence. This is one of Black's more harrowing, character-forming experiences.

Black writes very well -- he's vivid, dramatic, thoughtful, and articulate. As an extra bonus, on occasion, he discusses criminal vernacular and the sources of various underworld terms, including bum, yegg, pegged, dan, and others.

Anyone interested in the last days of the Wild West, hobo jungles, and criminal history should read this book.

.jpg)